ambassadors

As mind-blowing as they look, salt flats are merely a total waste of space. Nonetheless, one of them clearly stands out. Bonneville is close to California, looks superb and although a protected landscape, it’s been a race track for more than 100 years. Each year, on August’s hottest days, hundreds of men - and a few women - gather here to chase after numbers and after raw sensations.

Bonneville Speed Week is the yearly apotheosis for restless souls. And it’s motorsport at its purest. They all wrench like monkeys, and endlessly discuss about carburettor needles and superchargers before they can finally fire up their self-made machine and give it a go. Always at full throttle. The hottest two minutes of their life are worth every penny.

The idea behind this event is as simple as tomorrow. There are no duels, no slipstreaming, no complicated rules, no twists or turns. It’s not a race, and it’s hardly a competition. There’s not even a classification or a podium ceremony. These guys and girls just go straight ahead. There are no winners or losers. It’s only about going fast and breaking records.

The real world is outside

The real world is outside

These vehicles aren’t produced in R&D centres by the big manufacturers. They’re born in barns after hours of hard work, and nobody cares about originality or authenticity.

Take me to the danger zone

Most fatalities happen on motorcycles. When things go wrong on two wheels around here, they really do.

MOTORSPORT AT ITS PUREST

Speed week is not part of a championship, you can’t make a career out of it, sponsors are not lining up to finance the sport and there’s nothing to win, apart from the odd feather in your cap. Everybody who sets a new record and goes at least 200mph, receives a red one. Blue caps are handed out to those who break the mould on the exciting side of 300mph, and competitors who manage a record above 400mph get the coveted black cap. There not many of them around, though.

Blue cap owners can be listed on half a page and only ten black ones have been handed out throughout history.

“More people have visited the moon,” says timekeeper Mike. Despite the extreme speeds, this sport doesn’t appear to be very dangerous. After all, there are no corners to tackle and there’s not really something to hit when they lose control. Still, a few lives have been sacrificed on this altar of speed. Some after a car rolled. But most fatalities happened on motorcycles. When things go wrong on two wheels around here, they really do. And the nearest hospital is 120 miles adrift.

Bonneville is not the place to be if you own a Bugatti Chiron. If only because the salt would destroy the car forever. But even more because it’s boring as hell to chase after new records with a brand-new supercar.

Speed Week is all about amateurs. These vehicles aren’t produced in the R&D centres of the big manufacturers. They’re born in barns after hours. Pixar can’t make up what these participants have put on wheels and nobody cares about originality or authenticity. The relentless adapting and constant improving are what makes it so much fun.

Luckily, this event has almost as many classes as it has contestants. The secret to success is fine-combing the rulebook, unearthing the one category nobody ever cared about. The Hanson brothers did. They built a 750bhp Honda Civic which goes like stink. The front wheel drive turned out to have an extra advantage in this particular surrounding. “It guarantees much traction and the back just follows when the car becomes light at high speed,” they explain without much drama.

Someone else mounted a 1.5 litre Renault Clio diesel in a 50s Crosley microcar to create the world’s fastest small diesel truck.

And Team Stupid Baker made their name with a Studebaker Commander. “It has 960bhp – give or take a few – and I’ve spent more than my lunch money on a couple of days in a wind tunnel,” smiles the owner. In this game, it’s all about high power and low drag.

One participating Fiat 500 is longer and stronger than a 40-tonne truck, while a Triumph Spitfire is so shrunken down, the driver can only climb on board through the roof. Other self-made aerodynamic marvels are so flat and condensed, it’s tough to imagine they have wheels, let alone that they hide a big fat V8 and a driver with a comparable stance.

Marshalls: safety first

Marshalls: safety first

Because the Speed Week is an “unofficial” race, it’s totally dependent on volunteers.

Rule 1: There are no rules

Pixar can’t make up what these participants have put on wheels.

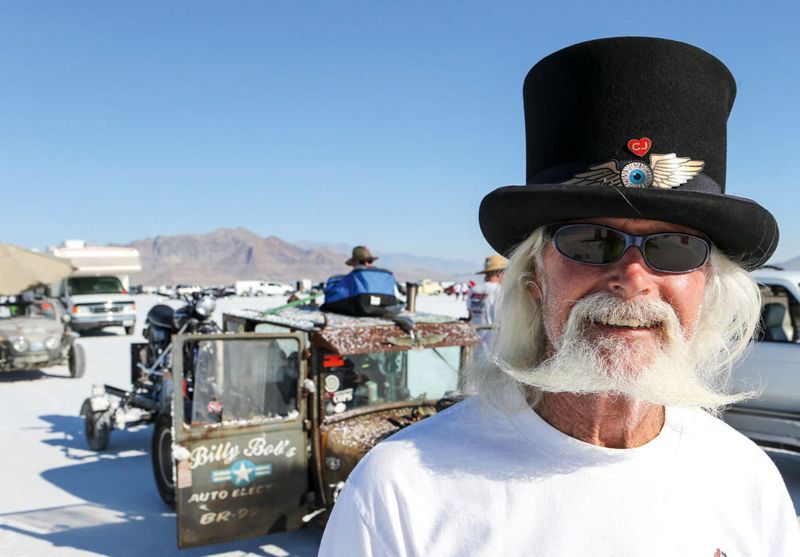

Speed Week is mainly famous because of the Hollywood movie “The Fastest Indian” starring Anthony Hopkins. He plays Burt Munro, an elderly loner who goes to great lengths to set a new record here. For once, the charming movie isn’t exaggerated. Because Burt Munro truly exists. There are hundreds of them, in all sizes and appearances. They’re all old or older, pickled, smoked and burned, with a smile like Fozzie Bear, and with wrinkles deep enough to hide another spanner. A 75-year-old with 49 participations under his tool belt is only average, and Fred touched both 276mph and his 85th birthday recently. “Youngsters aren’t used to improving their cars in order to win speed. They just buy a new 200mph Porsche. But we’ve been doing this for so long already, we don’t know any better,” explains 71-years-young Frank Kenney, a 2012 red cap perched proudly on his head. Frank did 208.974mph with his totally modified Opel GT. He could have gone faster, however. “I switched it off after four miles to make sure my partner could win a red cap the following year. Sadly, the engine exploded during his attempt and our car got destroyed by the flames.

SMILING LIKE FOZZIE BEAR

Six days of racing

These guys and girls just go straight ahead. There are no winners or losers. It’s only about going fast and breaking records.

Speed Week is not controlled by the FIA and the organisation hardly has sponsors or means. Participants don’t behave like stars and the public must be very motivated to enjoy this visual feast. It’s an endless drive to get there and there is nothing – literally nothing – within 150 miles. The event itself is pretty thrifty, too. There are no VIP rooms, experience packages, posh hotels or hip lounges. Only salt, big trucks, dodgy camper vans and the odd tent to supply the biggest luxury: a tad of shadow. There’s no fancy catering, either. One hut for water and a hamburger shack, that’s it. If you’re lucky, you’ll find a plastic chair.

Despite the unique ambiance, it’s one of the world’s most accessible forms of motorsport. Drivers only pay a 350-dollar registration fee. And spectators get in for free. There are almost no no-go zones, as long as you carry a CB radio to be able to hear all safety warnings. Starters, timekeepers, scrutineers and other officials are all volunteers, with a welcome as warm as a summer’s kiss. They’re as straightforward as this race track, and they’re here because nobody else wants to do it. But mainly because it’s a helluva lot of fun. They can hardly remember when they weren’t doing this. Which is enough reason to keep going.

THE OLD BOYS’ CLUB

Racing is waiting. Always. Everywhere. Here as well. The basic principal is pretty simple, though. Contestants can have a shot at their convenience. No appointments, no strict starting order, no maximum amount of runs. First come, first served. As soon as the track is clear, they can have a go. But not every vehicle comes off the line or disappears out of sight as smoothly as hoped. Definitely not when there are braking parachutes to be folded up. Certainly on weekend days, four-hour waits are not an exception in the world’s most colourful traffic jam in front of the starting line. “You can run three times on a good day. It’ll add up to 12 or 15 shots if you stay for the entire week. At two to three minutes per attempt, it’s much ado for little,” admits a regular.

“But the atmosphere is great in this old boys’ club.” The organisation carved out three tracks. A two-miler for rookies, a three-mile intermediate and the five-mile big one, which includes three miles to lose speed again. Hard braking is out of the question. It’s too dangerous and too damaging for the surface. It takes six weeks to prepare the track with a big scraper because the salt creates little waves during the year, as if it’s undulating. If it doesn’t flood, at least. For two years in a row, Speed Week had to be cancelled because the terrain hadn’t properly dried after too much rain. Also, the salt degrades at a distressing pace, and its thickness has shrunk from 90 to 50 centimetres.

While environmentalists blame global warming, the participants believe it’s the responsibility of the salt mining industry. But nobody really knows. “Each year can be our last one. In the good old days, they easily constructed a 12-mile course. Now, we’re happy with an eight-mile stretch,” explains another regular.

When the salt finally opens at 7am, all drivers are keen to go out and have a drive. They’ve waited so long now. And there are more reasons to get up early when the climate is still mild. It’s nice for the engines, which eagerly deliver an extra few bhp in cold air. It’s nicer for the drivers too, as they sit in their metallic cars like corned beef. The competition is thrilling for the few hardliners, yet totally incomprehensible for normal human beings. It’s barely possible to understand the ranking and more than watching, this sport mainly is a matter of hearing. As soon as a car gets of the line, all spectators and other competitors raise their head towards the sky. Will the driver dare stay on the throttle? Will the engine fire on all cylinders? Will he switch it off in time?

Even so, it’s a lively spectacle and the atmosphere is charming, like a feel-good movie. Certainly at the starting line. It’s very romantic how these flatliners stare into the distance, the engine rattling, barking and shivering, the adrenaline and gasoline pumping in equal amounts, and the starters performing a ritual full of pathos.

AN ENDLESS QUEST FOR SPEED

A few teams are spectacularly professional for a sport in which there’s no money to be made. And Renault returned with the Etoile Filante, 50 years after it set a few records straight. But the participants’ list consists mainly of old-timers who don’t have anything. Like Tim. He’s a car guy, but he opted for a self-made 100cc motorbike which is so low, it’s barely controllable at low speed. “Why? Because bikes are cheaper. We’re high class on low economy.” His wife can’t understand the fuss. So Tim brought a friend to lend a hand and to drive around in a rusty Beetle with a parasol on top. “We’re sleeping in a 1973 Dodge camper van I got for free, and I found most parts of my bike all around. The leather on the tank is from an old sofa, the saddle used to be a diving suit and the steering gear originates from a chainsaw.” Tim will never earn a red cap. His device is not even barely fast enough. But he hopes to get his name in the official books, just for the sake of it; 100mph would be a tad faster than the current record.

Tim is pretty sure it’ll work, as soon as he can perform a perfect run. Two minutes at 13,500rpm, that’s all it takes. However, he has only clocked 30 miles during the three years he’s been trying. The search for the ideal final ratio turns out to be endless. Luckily. What on earth would this roughrider do otherwise? How deep will he fall when he finally reaches his target?

There’s also Britt Palmer, who brought the world’s fastest motorhome to raise money for research on the Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Even though Palmer suffers from the disease himself, he drove his mad GMC here all the way from Denver. And after Speed Week, he will dismantle splitters and other aerodynamic aids to steer his frantic bus back home again. “It’s a 10-hour drive. I’ll do it in six. Fortunately, this baby is so smooth, I can bake pancakes in the back,” he says.

For once, Palmer gave the wheel to Steve Snow, a retired jet fighter pilot and the father of Julianne, a five-year-old girl who lost the battle against this awful affliction a few months earlier.

At the end of the week, a lot of fuel has been spilled. And more laughter. A few tears, too. Ten red caps were earned. And one black one. They can now only hope for decent salt next year. And that everybody will make it. Nothing else matters. Even for the guy who came here to spread the ashes of his deceased brother. “Because he was a true racer.”

No new and shiny supercars here Youngsters aren’t used to improving their cars in order to win speed. They just buy a new 200mph Porsche. But we’re we’ve already been doing this for so long, we don’t know any better. It’s a way of living.

Going high class on low economy. His wife can’t understand what all the fuss is about. Because he was a true racer. One guy came here to spread the ashes of his deceased brother. It’s all a matter of dedication.

Going high class on low economy. His wife can’t understand what all the fuss is about. Because he was a true racer. One guy came here to spread the ashes of his deceased brother. It’s all a matter of dedication.

A classic beauty Renault returned with the Etoile Filante, 50 years after it set a few records straight.

Words Bart Lenaerts - Images Lies De Mol